From Siberia to the West

A personal story of immigration and the people who made it possible

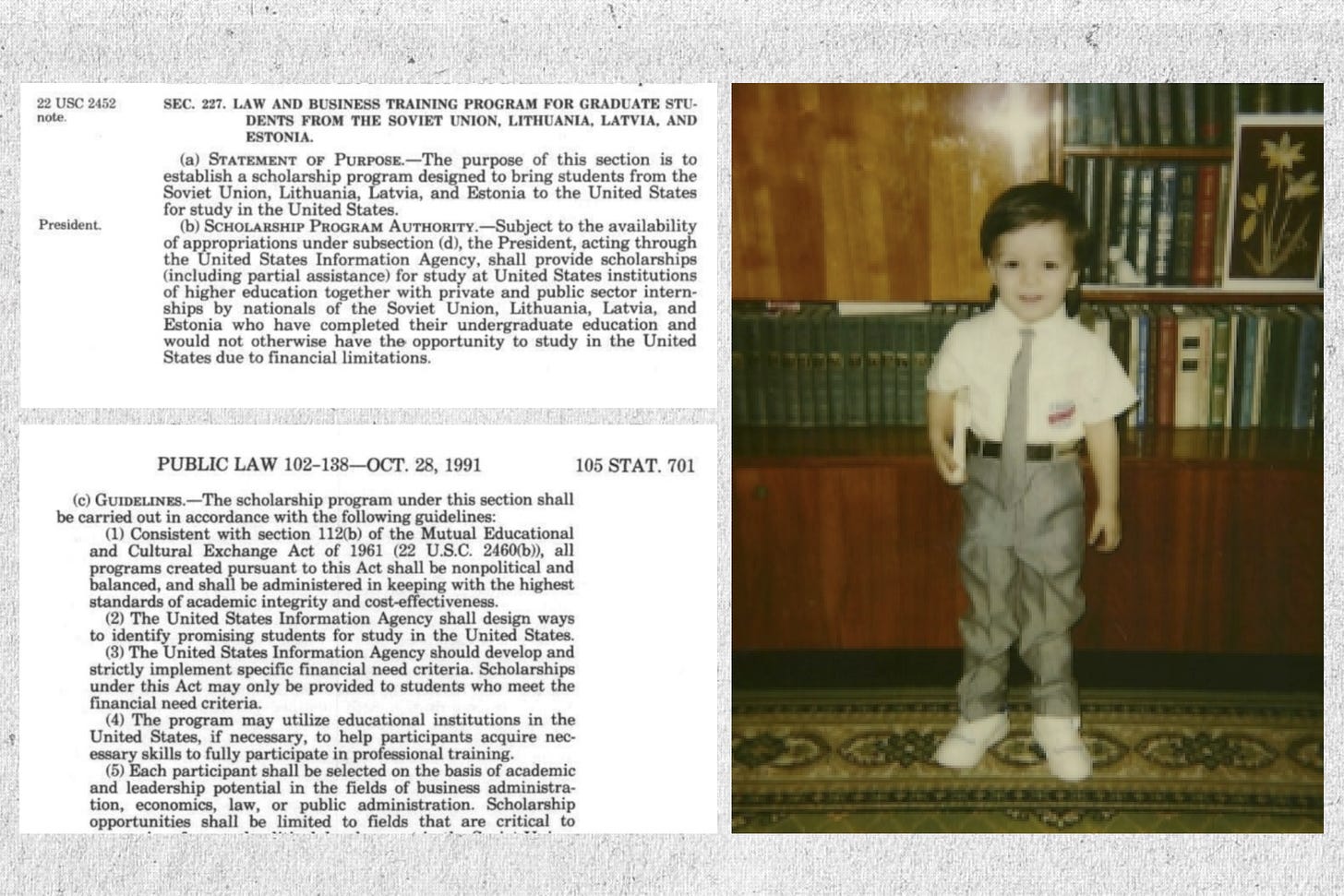

Somewhere in the archives of the 102nd US Congress, there is a provision that changed the course of my life.

Section 227 of the Foreign Relations Authorization Act (1992) established a scholarship for exceptional students from the former Soviet Union to pursue graduate degrees in the US. A year later, it was renamed the Edmund S. Muskie Fellowship.

That was the name on the program application that my mother filled out.

I didn’t know any of this growing up. I just knew my mom had been in America for 2 years studying when I was young, and that afterward, our world expanded. In 1999, we moved from an industrial town in the depths of Russian Siberia to London. I was six.

It was a before-and-after moment in my life. I came from a small town where very few people leave. At the time, I didn’t want to be one of them. While my grandma went to the embassy to get our visas, I remember sitting in my aunt’s kitchen praying that our application would get rejected. I was scared to leave the only world I knew. But I was also pragmatic, so I made a deal with God: if we did get our visas, at least let me learn English quickly when we moved.

This chain of events began years earlier with Senator Claiborne Pell of Rhode Island. As chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in the late 80s/early 90s, Pell was interested in human capital. He saw that while the Soviet command economy had produced brilliant scientists and engineers, it had suppressed the functions required for a free society: public administration, market economics, and the rule of law. He understood the importance of training the next generation of leaders.

He and his team did the work to set up this fellowship, bringing promising young professionals to American graduate schools. The program was born of an optimistic, confident time in US foreign policy. They felt the US had something worth sharing, and that bringing international students into its institutions would be mutually beneficial. They would immerse students in Western culture and values, trusting that those ideas would spread.

They named it after Senator Pell’s old colleague Edmund Muskie, the son of a Polish immigrant tailor who had risen to become Secretary of State. The symbolism was deliberate, and the program worked. On the macro scale, it produced leaders like Mikheil Saakashvili, who led the peaceful Rose Revolution in Georgia.

My mother was twenty-three when she came across the Muskie fellowship. We were living in the far east of Russia, closer to Japan than to Moscow, and somehow the application found her. She was brilliant, and she saw the application for what it was: an opportunity. Accepted into the highly competitive program, she flew to New York to earn her degree. I stayed with my grandparents, too young to understand what an MBA was or why she needed to go so far away to get one.

In New York, she met an older American couple named Bart and Pat, who took a shine to her. They were curious about this intelligent young woman from a country they had been told to fear their entire lives. They took her in, showed her how to make it in the big city, became something like family. When the program finished, they worked hard to introduce her to potential job connections. Through them, she met a woman named Sally, who helped her secure an interview in London. She got the job, and a couple of months later, I was in my living room praying for a visa outcome.

We got the visas. And although my first prayer went unanswered, the second was granted: while I was still in Russia, Bart and Pat sent me a new Nintendo Game Boy with Pokémon Red. I remember sitting on our kitchen floor, spending hours entranced by the game and inadvertently learning English (I mostly picked it up from a mix of Pokémon and Friends).

A few months later, I moved to London. I grew up there, learned the language, went to school, and built an expansive life in a world that would have been unimaginable from that kitchen floor. Eventually, I too went to New York, studying and building my career there for over a decade. When I got the opportunity, I became a US citizen. Full circle for the son of a Muskie Fellow.

It is hard to see something personal in a piece of legislation. Policy is inherently abstract, drafted in terms of statecraft and budget lines. But downstream from those decisions, individual lives are meaningfully and permanently changed.

I’ve been grateful to my mother my whole life for being brilliant and driven enough to get us out. Recently, I’ve started feeling gratitude to the people upstream: the senator from Rhode Island who believed education could change a country, the staffers who drafted Section 227, the administrators who processed one more application from the far east of Russia. They couldn’t have foreseen the individual impact of the chain of events they set in motion. A bill becomes law. My mother gets accepted. Bart and Pat take her in. Sally makes a call. A young boy moves West. And here I am, twenty-five years later, tracing the story back to the source.

I think about that six-year-old on the kitchen floor a lot. He was so scared and had no idea what was coming. I wish I could tell him, don’t worry, you’re about to have the most wonderful adventure.

With love,

Timour

Beautifully written and beautifully lived!

Such a beautiful piece! Made me emotional!

"It is hard to see something personal in a piece of legislation", is such a great framing.