Prototyping the future at the edges

Six examples of historical experiments that reimagined society

Hey friends, Timour here. I’m one of the founders of Edge City, and this year, I’m hoping to be writing more, sharing the journey of building our ecosystem and exploring the ideas shaping it, from societal experimentation to technology, governance, and emerging cultures.

Paradigm shifts often start at the edges. Throughout history, people have carved out space outside the mainstream to exchange ideas, explore new ways of thinking, and reimagine what’s possible. From Enlightenment salons to Auroville, these hubs of exploration have shaped the world in ways that lasted far beyond them.

Today, popup cities continue that lineage. For a month at a time, 1,000 people come together to prototype new ways of organizing society, exploring everything from governance experiments to decentralized technologies to alternative ways of building community. They aren’t just spaces to talk about new ideas; they’re places to live them.

(If you’re thinking, what on earth is a popup city, I wrote about my experience at Zuzalu and why I’m so excited about this format here: Zone of Scenius.)

The excitement around this is growing. Last November at DevCon, I cohosted a session on this movement with Janine (my cofounder at Edge City), Nicole, and DC. The room was packed, and a dozen folks stayed afterward to discuss starting their own popups. It’s exciting to see the momentum.

I opened the session with a 10-minute talk situating popup cities in a broader context—a lineage of human creativity in rethinking how society works—by sharing six of my favorite historical examples. The tldr is that humans have always had amazing creativity and agency in imagining better worlds, and we need to continue that tradition.

Right now feels like a particularly important time for this kind of experimentation. Tech is moving fast; society isn’t. The coming wave of change will force us to rethink core questions, like:

Should there be a new social contract in a world with strong AI? What should it look like?

How do we ensure new technologies enhance human flourishing rather than undermine it?

How do we design governance systems agile enough to keep up with exponential change?

There are many others. Where will answers come from? Some will come from the usual places: universities, think tanks, the public sector, and corporations. But those institutions work within existing structures. They refine ideas, but they don’t create new worlds. Popup cities let us do that.

History serves as inspiration. You can watch the talk (10 mins), or for those of us who still prefer to read, below is a summary of the examples I shared.

Historical Examples

Enlightenment Salons (17th–18th Century, France)

Founded: 17th–18th century, primarily in Paris.

Notable Participants: Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot; hosted by influential women like Madame Geoffrin and Madame de Staël.

Description: Social gatherings where intellectuals discussed philosophy, politics, and science in informal but structured environments.

Ideas/Technology: Sparked the development of revolutionary ideas like liberalism, democratic governance, and the concept of universal human rights.

Imagine a firelit room in 18th-century Paris, the home of Madame Geoffrin. The city’s brightest minds, a mix of philosophers, writers, and statesmen, are gathered in heated discussion. They drink wine, argue about Rousseau’s latest essay, and debate whether monarchy can survive the century.

These salons weren’t universities or formal institutions, yet they shaped history. They provided a rare space for intellectuals to push the boundaries of accepted thought at a time when questioning authority could be dangerous. It was in these small gatherings that ideas like democracy and human rights were incubated and refined. It’s easy to forget how radical these concepts once were because they’ve been woven so deeply into modern life. But none of them were inevitable; they started as conversations.

To me, this is a reminder that big shifts often start in small rooms. Today, instead of books and pamphlets, new ideas spread through blogs and group chats. But the principle remains the same: we need spaces to debate and refine the core ideas that will shape the future.

The Chautauqua Movement (1874–Present, U.S.)

Founded: 1874, Chautauqua, New York, by Lewis Miller and John Heyl Vincent.

Notable Participants: Speakers included Mark Twain, Susan B. Anthony, and William Jennings Bryan.

Description: Initially a lakeside retreat, it evolved into a national movement blending education, arts, and recreation. Local communities hosted traveling Chautauqua events that brought lectures, music, and discussions to rural areas.

Ideas/Technology: Pioneered participatory education and broadened access to cultural and intellectual resources.

In 1874, a small group gathered on the shores of Chautauqua Lake for what was supposed to be a one-time summer retreat. Soon, “Chautauquas” spread across the country, creating traveling circuits that brought education, music, and debate to towns across the US. These events were temporary public learning festivals, giving people across the country access to intellectual and cultural opportunities they couldn’t find elsewhere. Notable figures like Mark Twain and Susan B. Anthony spoke at these gatherings.

What’s interesting about Chautauqua is how it scaled; what began as a single event in upstate New York turned into a decentralized network of gatherings that persisted for decades. This is a clear parallel to what is happening with popup cities, which started as temporary gatherings and are now going global. Our collaborator on Edge Esmeralda, Devon Zuegel, has written beautifully about her experience of Chautauqua as ‘an idea embedded in a place.’

Black Mountain College (1933–1957, U.S.)

Founded: By John Andrew Rice in North Carolina as a radical alternative to traditional education.

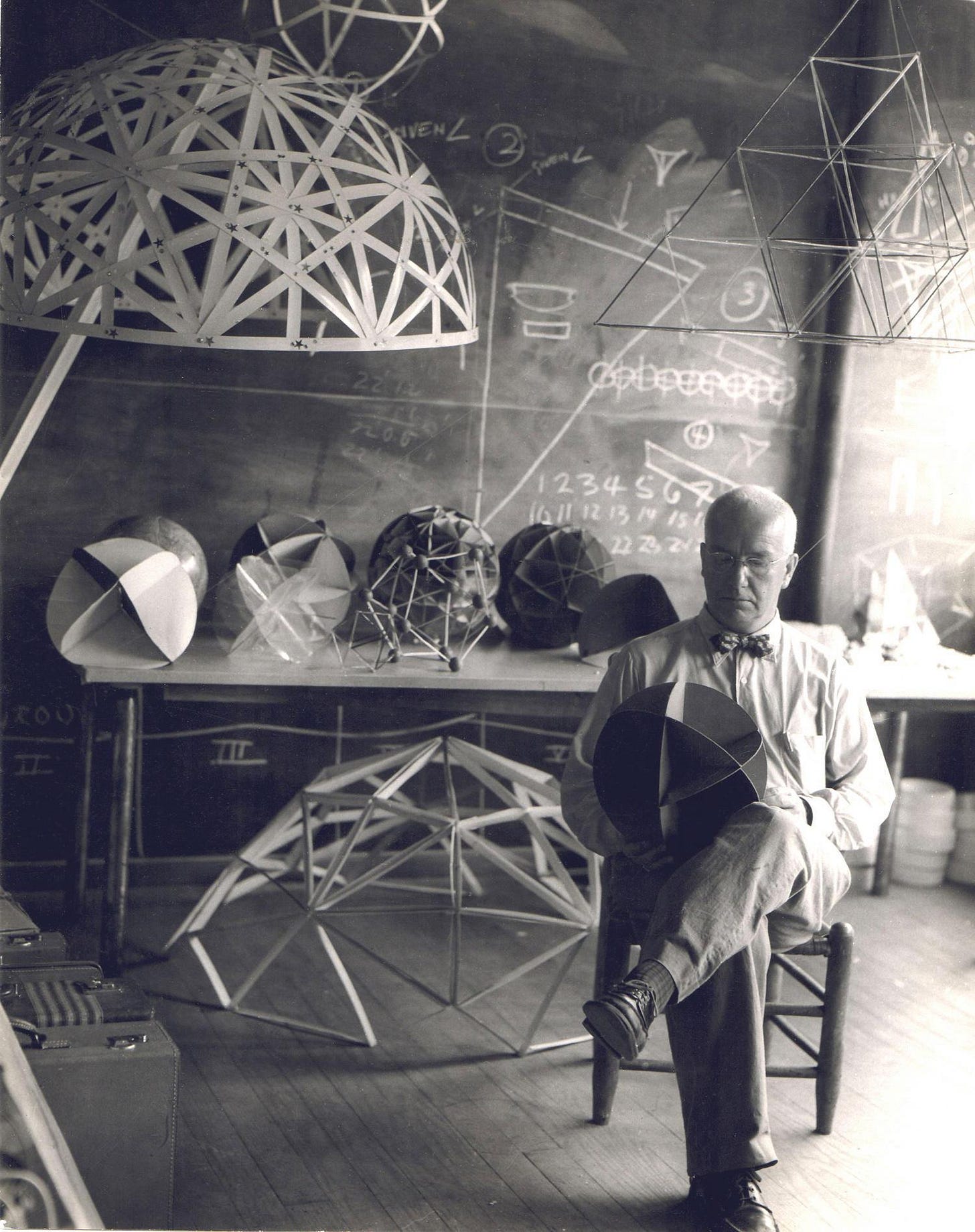

Notable Participants: Buckminster Fuller, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Willem de Kooning.

Description: A progressive school that blurred the lines between living, learning, and creating.

Ideas/Technology: Produced groundbreaking work in architecture, art, and music. Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome, for instance, became an icon of sustainable design, while Cage’s experimental compositions redefined music.

Before Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome became an icon of sustainable design, it was an experiment at Black Mountain College. Before John Cage redefined music, he was testing his ideas in its studios. This small, unconventional school in North Carolina became a breeding ground for ideas that would shape art, architecture, and beyond.

Black Mountain College rejected the hierarchy of traditional universities. There were no deans, no rigid departments—just a belief that learning happened best when people worked side by side. Its multidisciplinary approach fostered an environment where ideas collided and evolved into something entirely new. It was an attempt to dissolve boundaries between disciplines, and between education and life. This aspect is definitely something we’re inspired by at Edge City.

Although Black Mountain College was a permanent institution, for many people, their experience was temporary (similar for Auroville and SFI below); they could come for a summer or a semester to go deep on a particular idea. It is inspiring to us to think about how, over time, edge cities can become permanent hubs as well.

Auroville (1968–Present, India)

Founded: 1968 by Mirra Alfassa ("The Mother") with inspiration from Sri Aurobindo’s philosophy.

Description: An international township in southern India designed as a living experiment in human unity, sustainable living, and decentralized governance.

Ideas/Technology: Pioneered eco-village concepts, renewable energy systems, and new governance frameworks for global communities.

In 1968, thousands of people gathered in a barren stretch of land in southern India for an unusual ceremony. They came from all over the world, carrying handfuls of soil from their home countries, which they placed into a marble urn at the center of a newly founded settlement: Auroville. It was meant to be a place beyond borders, beyond money, beyond religion; a living experiment in human unity.

What makes Auroville remarkable is that it still exists more than 50 years later. Utopian projects tend to collapse under their own weight, but Auroville continues to evolve, testing new models for living that inspire many other experiments around the world. They have thousands of residents from dozens of countries who work on regenerative agriculture, renewable energy, and alternative governance systems. It’s one of the most ambitious attempts to create a self-sustaining, borderless community.

I think Auroville is a great reminder of how radical experiments, while challenging traditional norms, can inspire lasting change, both locally and globally. We had folks from Auroville come to Edge Esmeralda, and it was exciting to see how enthusiastic they were about the concept of popup cities. From our conversations, it seems like their experience with Auroville made them particularly keen on the idea of creating spaces for real-world experimentation with new ways of living.

Santa Fe Institute (1984–Present, U.S.)

Founded: 1984 by scientists, many of whom had worked on the Manhattan Project.

Description: A research institute dedicated to understanding complex systems through interdisciplinary collaboration.

Ideas/Technology: Advanced complexity science with applications in economics, biology, climate science, and social systems.

Why do some civilizations collapse while others endure? Why do financial markets behave like ecosystems? Why do weather patterns resemble the spread of disease? These questions are fascinating, yet academia isn’t designed to tackle them directly. The most interesting problems don’t fit neatly into physics, biology, or economics; they live in the gaps between them. So in 1984, George Cowan gathered a group of scientists in Santa Fe to create something new: a research institute dedicated to multidisciplinary study. Something they would eventually call complexity science.

This radical approach worked. Over the next few decades, Santa Fe researchers pioneered new ways of thinking about networks, chaos theory, and adaptation. Their work reshaped everything from financial modeling to epidemiology, proving that the biggest insights come from seeing the world as an interconnected system.

What inspires me most about the Santa Fe Institute isn’t just that they were multidisciplinary; it’s the intentionality with which they approached it. They didn’t just hope for breakthroughs; they thought incredibly hard about how to maximize the likelihood that they would happen. Through structured workshops and deliberate cross-disciplinary collaboration, they made interdisciplinarity real. We’re taking that same principle at Edge City but expanding it beyond intellectual fields into technology, science, and culture. If SFI is about interdisciplinary thinking, we want to cultivate interdisciplinary doing. It’s a tall order, and I have humility in that. We have a lot to learn, but we’re excited about the challenge.

For people curious to learn more about SFI, I highly recommend the book Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos, which was recently suggested to me by Ryan Pripstein, who thoughtfully intuited that there are a lot of lessons for us in the story of the institute.

Burning Man (1986–Present, U.S.)

Founded: 1986 by Larry Harvey and Jerry James; now held annually in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert.

Description: A temporary city built on principles of radical self-expression, self-reliance, and participation, combining art, community, and experimental living.

Ideas/Technology: Fostered participatory culture, large-scale art installations, and experimental living systems.

If you take the term popup city literally, Burning Man is probably the first thing that comes to mind. For most of the year, Black Rock City is nothing but desert. Then, for a brief moment, it transforms into a self-organized city of art, radical self-expression, and community. What started in 1986 as a small gathering on a San Francisco beach—just a few friends burning an effigy—grew into an annual festival, then into a global movement.

I’ve had many meaningful experiences at Burning Man, and I’m often struck by how a short event can leave such a lasting imprint on culture. I recommend it to anyone who can swing it and feels called to go—I’m always in awe at people’s creativity when I’m there. “I can’t believe someone thought to do that and then went for it” is a common refrain.

That said, there’s an important distinction between what happens at Burning Man and what we’re trying to build with Edge City. The festival excels at fostering creativity and self-expression, but it’s designed to be a full escape from the default world. We’re interested in something different: how the energy, experimentation, and community of a temporary gathering can prototype and actually incubate real-world institutions, technology, and culture. Burning Man proves that short-lived environments can be transformative. The question we’re asking is: how do we carry that energy forward into the way we live, work, and build long-term?

Other Examples

Many other experiments would work as examples, some of which I may explore in future essays. Below are a few quick honorable mentions.

The Esalen Institute in California became a nerve center for the countercultural movements of the 1960s and 70s, pioneering breakthroughs in psychology, human potential, and alternative ways of living. The Bauhaus School redefined art and design by embedding experimentation into daily life, merging craftsmanship with modern technology in ways that still shape architecture and design today.

Looking further back, Michel Bauwens shared an example with me that I find fascinating: after the fall of the Roman Empire, medieval monasteries became places where monks preserved knowledge and ideas about how society could function, laying the intellectual foundations for Europe’s revival.

Nowadays, many others are experimenting in this space, each with their own approach. Feytopia, Cabin, Network School, and the various Zuzalu-inspired villages are part of a broader wave of decentralized, experimental communities. Some focus on governance and technology, others on creativity and culture, but all share a common impulse: to explore new models of living and working together. It feels like we are entering a golden age of societal experiments—one where people are no longer waiting for change to come from existing institutions but are building new structures themselves.

Why does this matter?

“The ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently.” - David Graeber

I love this quote from Graeber because it’s so obvious and so easy to forget. We inherit institutions and norms, but we’re not stuck with them. Every generation has its challenges, but it also has its opportunities—moments where we get to ask new questions about how to live well and then create the systems around us to reflect those answers. And when things feel uncertain, that’s usually a sign that something new is emerging.

That’s what excites me about popup cities. They aren’t about forcing a vision of the future; they’re about creating environments where people flourish and then seeing what emerges from that. Think about what can be incubated in communities where people are energized, flourishing, and engaged in experimentation together.

We have a long long way to go. A lot of the experimentation focus I mentioned above is aspirational; it takes time to figure out how to organize and grow any novel idea. I don’t know what will emerge out of all this, but that’s what makes it fun. If you want to be part of it, come hang out at Edge City ☀️

You may appreciate https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/57450905-the-utopians

Love it. Some other examples that spring to mind for me are the bauhaus and arco santi.